Exploring the Link Between Cocoa Farms and Biodiversity

That chocolate you’re eating? There’s a good chance it came, in part, from Africa. The continent produces more than 70 percent of the world’s cocoa supply, mostly from small-scale, shade-grown farms in west and central Africa.

Most cocoa trees need some shade to prosper. So on these plantations farmers leave, or plant, some non-cocoa trees. Traditionally, farmers plant fruit trees as shade, or simply leave tall rainforest trees at random. While research has shown farming cocoa among shade trees canboost species diversity, questions remain about just how it impacts the food web, and how to best balance the needs of agriculture with the local biodiversity.

CBI affiliate Luke L. Powell, director of the conservation NGO Biodiversity Initiative and a research fellow at Durham University in the United Kingdom, is deploying cutting-edge metabarcoding technology to help answer those questions. Metabarcoding combines two different technologies – DNA-based identification and high throughput sequencing – to rapidly identify the taxonomic diversity of different ecological communities.

“We want to build a framework where you use metabarcoding to understand the ecosystem,” Powell said. “To make a map of the food web, in a very literal sense.”

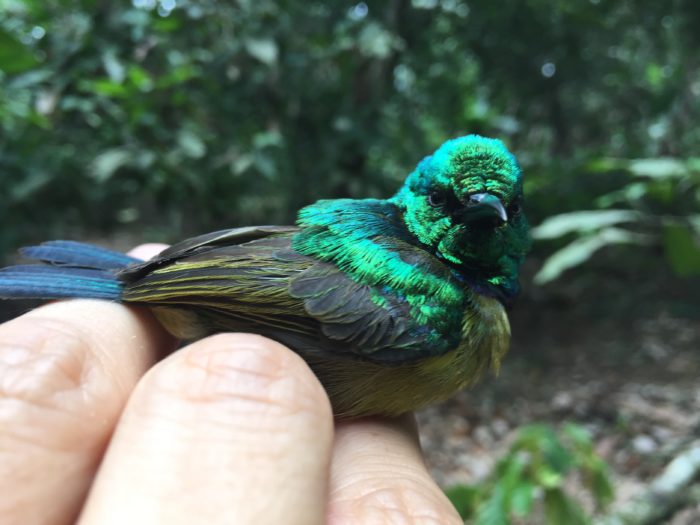

Powell and his team, which includes Cameroonian graduate students, recently spent two weeks in Cameroon, surveying over a dozen cocoa plantations. They took feces samples from more than 500 birds and bats; metabarcoding will allow the team to identify dozens of arthropods in the sample. Basically, to figure out what species of insects and arachnids the birds and bats eat. A rice-grain sized feces sample averages at least 23 unique prey items, Powell said.

Food webs – the feeding relationships within an ecological community – are often astonishingly complex. Metabarcoding can reveal these webs in incredible detail.

“The technology also picks up DNA from tree leaves that were eaten by the insect, and then eaten by the bird,” Powell said. “We can figure out which are the keystone trees – the oaks of Africa – that support huge number of insects, which ultimately supports the animal community.”

And the technology could work far beyond Cameroon and cocoa. “Mosquito control for Zika in Brazil can use this exact framework,” Powell said. “You can understand how you can specifically manage the ecosystem to increase the number of birds or bats that predate [on mosquitos carrying Zika].”

In addition to CBI, Biodiversity International, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), and a UK Research Fellowship from Durham University are also supporting this research.

Check out the pictures below to see some of the birds and bats Powell and his team sampled during their recent field work.